Robert Smithson as a social critic

ROBERT LINSLEY

In information theory you have another kind of entropy.

The more information you have the higher degree of entropy, so that one piece of information tends to cancel out the other.1

This quote, from a 1973 interview, should serve as a warning to students of Robert Smithson’s work. According to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, a local increase of order within a closed system is negated by a net overall increase of disorder in that system. Attempts at clarifying Smithson’s thought, with its multitude of openings and references, all too often only enlarge a "mineral dump" of documents, agglomerated with footnotes and predictable citations, that ultimately only refer to each other. In this study I will focus on the places where Smithson’s thought reaches out beyond his own works and their conceptual interrelationships to the social world. In this way I will skirt the edges of the morass, but in no way do I claim to circumscribe Smithson’s art. Although Smithson evidently did not want his writings to be considered artworks, in fact they do form a continuum with his sculpture. Nowhere in Smithson’s work do we find any discrete or closed entities. It was Smithson's genius, working in a period that believed above all in the self-referential ity of art, and in the irreducibility of "the thing itself," to be absolutely of his time, and an important figure within it, and yet to transcend many of its limitations.

According to Lucy Lippard, Smithson . . exposed social implications that had previously been buried in aesthetics."2 She found these implications in Smithson’s earthworks, particularly his conflicts with ecologists and his concept of the "dialectical landscape." Although his earthworks, beginning with the so-called "non-sites," are the decisive development for Smithson as a critical artist, I propose that a social critique is also inherent in his theory of Minimalism, and in fact in all of his work from the publication of his first major essay, "The Crystal Land," in 1966. My paper chooses a path through three years of Smithson’s work, from 1965- 68, starting with his discussion of Minimalism and concluding with the non-sites. This is a section of Smithson’s route from the city out into the wilderness, from his early urban based Minimalist sculpture to his later monumental landscape pieces. To the extent that the non-sites themselves are a kind of Minimalist sculpture which links the suburban margins with the urban centre, this path turns back on itself, like a spiral.

Smithson’s insights into modern experience, expressed concretely as sculpture, or through the many layers of associations and literary references built into his writings, illuminate a world that is familiar to all of us, yet has the property of being able to defeat its own representation; a world that wears a cloak of invisibility even as it presents the most banal and obvious surfaces. It was in the nineteenth century that the modern city assumed its distinctive character both inside and out, and the modern artist his twin role in response to it. Internally, the city began to form around the street as a channel for the movement of traffic rather than the market square as the site of social interaction. For the passing crowd, the city presents itself as a spectacle of consumption and a spectacle to be consumed, and in this milieu the artist became the flaneur, detached and critical. Externally, in the suburbs, where the growing city devours nature and expels its waste, where all kinds of activities coexist in an incoherent jumble, the landscape painter sets up his easel.3*Smithson takes up both of these roles in his own way. As a cultural critic and flaneur he contextualized Minimalism within the contemporary architectural environment and traced a lost social history in the architecture of the thirties. As a contemporary landscape artist, he traveled to the outskirts of the city, which he "represented," first in descriptive articles, and then in his sculpture, which by bringing fragments of the suburbs into the urban gallery, linked these two spaces materially rather than through the "idealist" mediation of a picture. In tackling the problem of the representation of the urban environment, Smithson took up and reinvented, perhaps unknowingly, the tradition of modernism that takes modern life as its subject, and in so doing placed himself in opposition to the dominant tendency in post-war American art which proposed an organic development of art as progressive self-definition.

His argument with formalist theory, although expressed differently at different periods, dates back to his earliest work. Smithson entered the New York art world at the end of the 1950s. His emergence coincided with the first public recognition of the Beats, and he joined a milieu that included Beat writers. His painting at that time was influenced by Abstract Expressionism, but he early took issue with the theory that described that work as a formal breakthrough. For Smithson, the biomorphic was to be seen just below the surface of Jackson Pollock’s drips and skeins. His criticism of the critical dogmas of the New York school was accelerated by his reading of T.E. Hulme, and Hulme’s own mentor as an art critic, Wilhelm Worringer. As he began, following Worringer’s ideas, to imagine an abstraction based on inorganic natural forms as a countermovement to Abstract Expressionism, he was drawn towards the Minimalists.4 By 1965 he had begun to write about their work in terms of entropy, a concept drawn from the physical sciences.

The Three Laws of Thermodynamics were a nineteenth-century discovery. Together with other scientific insights of the period, such as Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and Charles LyelTs interpretation of geological strata, they formed part of a constellation of new ideas that posed a serious challenge to Christianity. In the nineteenth century all major scientific discoveries were understood to have ramifications for social theory because they struck at the foundation of universal concepts that had guided social life up to that point. The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that in a closed system, the distribution of energy will tend toward equilibrium, or maximum entropy. Since the universe is finally the only closed system, the principle of entropy, as the Second Law is commonly called, predicts the ultimate end, or "heat death" of the universe. In the century that discovered evolution and fell in love with the notion of progress, the Second Law fed into a pessimistic countercurrent that saw progress as decay. As if to fill a psychic void left by a departing faith, the vision of the heat death of the universe, the final triumph of entropy, became a scientific eschatology, but one that was never far from present concerns. Smithson probably first encountered entropy in the novels of H.G. Wells, whom he cited as an important childhood influence.5 In Wells’ novel The Time Machine, the hero travels to the far future where he finds that the social classes of the nineteenth century have evolved into separate subspecies of humanity, and that each has further devolved to the level of amnesiac reflex. After escaping the nightmarish clutches of the devolved working class of the future, the hero travels forward to the end of time, to see the bloated red sun looming over the dying earth, the entropic finale of all life. The Time Machine is a social satire in the Swiftian tradition, but it is also a serious meditation on the notion of progress as decay.

Yet though the idea that increasing specialization of social functions can lead to an overall breakdown of society is informed by entropy, when Wells explicitly introduces the Second Law it is as a cosmic principle to which all social life is ultimately subject.6

The time machine itself is not just another marvelous invention among the many projected in scientific fantasies of the period, most soon to become banal realities, such as airplanes, submarines, and so on. It is a literary device by which the author can propose the past and the future as real places that actually exist. Yet since the imaginary future can only be an extrapolation of the present, an image of a succession of future times resembles an infinite perspective of distorted images of the present. This kind of delirious concretization of the imaginary would have great significance for Smithson’s own Minimalist sculpture. It also serves a real descriptive function, for scientific speculation about the future is rooted in present observations. As the Victorian mind, propelled by the energy of scientific discovery, reached into the beginning and end of creation, it formed fantasmic, provisional, yet very clear and concrete images of distant times. Though actually impossible, the concept of time travel was an imaginative necessity as a self-description of the adventures of the scientific mind.

Science fiction became a mass culture phenomena in the United States in the 1920s and 30s. Brian Aldiss, science fiction writer and historian, has traced the persistence of certain motifs, specifically entropy, from the work of nineteenth-century writers such as Wells into American pulp science fiction.7 A huge proportion of this literature was preoccupied with entropy, and full of cliched images of evolution and devolution in uneasy combination layered over a cosmic backdrop.8 In the 1940s, however, this popular writing became increasingly positivistic; the huge time scales began to shrink, entropy was forgotten, and the utopian content of early science fiction was suppressed in favor of realistic descriptions of technical problems. Smithson, through his many citations, reveals a preference for the earlier science fiction, some features of which survived in "B" movies. His recovery of the concept of entropy from a nearly forgotten literature, entangled as it always had been in that literature with a social history, represents the recovery of a pessimism that was largely unknown in post-war America, particularly the notion that technical progress is linked with social decay.

The concept of entropy has had one life in literature, it enjoys a different sort of existence in science, fills another role in social thought today, and yet another in information theory. The different meanings of entropy in different contexts often stem from a linguistic confusion. Smithson’s application of entropy to art drew from all of these interpretations of the concept and incorporated an understanding of the imprecision that often surrounds it. An important scientific reference for Smithson was P.W. Bridgman’s authoritative The Nature of Thermodynamics, reprinted in 1961. Bridgman was very interested in the ways that the formulation of physical concepts depended on the language used to talk about them, implying a certain arbitrariness in those concepts that reflects the subjective interests of their framers. Bridgman’s own particular formulation of entropy has resonance in Smithson’s writings. For Bridgman, "Isolated systems seek a dead level." He also observes that . . when the dead level is reached, no work can be extracted."9 To talk of primary structures as entropic, as Smithson did, is to reiterate their complete social uselessness. They have achieved a dead level of . . delayed action, inadequate energy, general slowness, an all over sluggishness/'10 The boredom and inertia radiated by Minimalist objects is an implicit critique of a society dedicated to ambition, hard work, progress and development. These works are obstacles in the forward flow of American life. Smithson’s terminology also places these works in opposition to gestural abstraction; an allover sluggishness replaces an all-over "action painting."

Barbara Rose, in her article "ABC Art" of 1965, also saw the critical content of Minimalism in its negativity. She notices how Minimalist works . . blatantly assert their unsaleability and functionlessness/' The . . negative art of denial and renunciation . . is . . out of step with the screeching, blaring, spangled carnival of American life."11 In America, land of the go-getter, Minimalism is the expression of a fatalistic, passive opposition, and for Smithson, entropy is its rationale.

Smithson could have been provoked to link Minimalism and entropy by a comment in Bridgman’s book:

Thermodynamics makes no attempt to give a rating to the relative order of the paintings of a da Vinci or a Turner, and certainly does not attempt to attach an entropy to a work of art. In fact, there is a school of art, that of the Futurists, which would use 'disorder’ in a sense to give exactly the opposite results from thermodynamics. It is said by some that this school sees the prototype of beauty in anything of complete naturalness. Hence to this school the drive of the universe toward the complete chaos of molecular disorder must appear as the height of all beauty, and therefore of the highest order.12

Bridgman’s own misunderstanding of the futurists is an example of the conflation of different concepts under the heading of entropy that he himself discussed, and this discussion gave Smithson the material for some entropic humor in his own writing.

In information theory, entropy means the tendency for errors in communication to increase. Increasing error means increasing disorder, but Bridgman, with his attention to the language used to describe phenomena, observes that . . there is a rather large verbal element in the coupling of 'disorder’ with entropy, and that this coupling is not always felicitous/’13 Bridgman brings forward the example of a crystal, which forms from a cooling process and therefore represents a decrease in disorder although an increase in entropy. Bridgman explains that . . disorder is not a thermodynamic concept at all, but is a concept of the kinetic-statistical domain."14 The regularity and stability of a crystal mark it as the final state of a chemical process, without potential for further transformation. But Bridgman also points out that there are exceptions. He brings forward the example of " . . . a quantity of sub-cooled liquid, which presently solidifies irreversibly, with increase of entropy and temperature, into a crystal . . . Statistically, of course, the extra 'disorder’ associated with the higher temperature of the crystal more than compensates for the effect of regularity of the crystal lattice.’’15 This is a special case, that of a liquid cooled below its freezing point that stays liquid until its crystallization is triggered. This absurdly recondite scientific discussion gives Smithson the opportunity to sow a little confusion himself. In "Entropy and the New Monuments" the following quote from Bridgman is an apparent non sequitur, inexplicable in relation to what precedes it: "But I think nevertheless, we do not feel altogether comfortable at being forced to say that the crystal is the seat of greater disorder than the parent liquid/, 16 Smithson then completes the linking of Minimalism, entropy, and crystals by observing that . . the formal logic of crystallography relates to Judd’s work in an abstract way/,17 We will see that this linking opens out into a rich field of social meanings when we realize that he has used Bridgman to draw our attention to the "parent liquid."

In a piece called "The Crystal Land," published about the same time as y/Entropy and the New Monuments," Smithson recounts a visit he, Judd, and their wives paid to a quarry in New Jersey. From the quarry, in a kind of suburban no-man’s-land, Smithson can see housing developments:

. . . on and on they go, forming tiny box Iike arrangements.

. . . The highways criss-cross through the towns and become man-made geological networks of concrete. In fact, the entire landscape has a mineral presence. From the shiny chrome diners to glass windows of shopping centres, a sense of the crystalline prevails.18

Numerous citations throughout the 1960s and later point to a relationship between Minimalist sculpture and contemporary architecture. At first this work was received as a critical analysis of the exhibition space.19 Dan Graham and Smithson were two artists associated with Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd, and Robert Morris who explicitly drew a parallel in their writing between Minimalism and the architecture of the city in general. Graham’s "Homes for America," published in 1966, about six months after Smithson’s writings just cited, analyzed suburban tract housing in terms of discrete modules or boxes, permutated in a limited series of predetermined variations, something like what one would find in a work by Sol LeWitt.20 Smithson for his part linked Minimalism with . . the vapid and dull with the . . lugubrious complexity of the interiors . . . of discount centres and cut rate stores . . . such as are found near superhighways surrounding the city.’’21 According to Smithson, the "The slurbs, urban sprawl, and the infinite number of housing projects of the post-war boom have contributed to the architecture of entropy."22

Minimalism, entropy, architecture, and crystals, all interrelate in Smithson’s thought. Each of them lies on an axis with one of the others, perhaps forming a crystalline shape. Entropy recovers its original social implications through its linking with architecture, and these implications resonate through the whole formation.

Minimalism can only really be called critical when its foregrounding of the exhibition space opens out into an analysis of the social relations inscribed in that space. A phenomenology of gallery spaces is rendered critical by virtue of qualities inhering in the Minimal object, such as the negativity and inertia noticed by Smithson and others, and by virtue of an art world context that supports an ongoing social discussion. To assume that these conditions are always present is to take a lot on faith. The relationship between the work of Judd, Morris, Flavin, and LeWitt and the larger culture is not spelled out by the artists, neither is it always evident in their work, and a critical interpretation of that relationship is contingent on specific exhibition contexts. For Smithson, Minimalism seems to be less critical than ideological. Crystals precipitate out of a solution and grow automatically according to the logic of their construction. The social meaning of primary structures lies in this inevitability and, in an ideological sense, unconsciousness. In the crystalline world, art doesn't so much reflect an image of society as it is society's own perfect product, a precipitate from the social solution the "parent liquid."

So far I have drawn exclusively from Smithson’s writing, which in contextualizing Minimalism, also makes an implicit critique. Smithson never writes metaphorically with respect to the important ideas I’ve mentioned. He is concerned with observable phenomena of the physical world, to which Minimalist objects belong. 니ke Judd and Morris, he is interested in the art object itself and its properties, but unlike them he sees these objects in relation to other objects that form the social landscape. Though certain of the properties he recognizes in Minimalism are invisible, they are nonetheless real. The entropy or lack of potential of Minimalism is real, it is not a metaphor, and neither is the effect that this work has on the spectator’s experience of time.

The irreversibility of entropy is the irreversibility of time. As Sir Arthur Eddington put it, "Entropy is time’s arrow/’23 The achievement of a universal static condition of maximum entropy is the end of time. Where Smithson notices the precipitation of objects devoid of potential, entropic end-products, from the flux of contemporary life, he observes that the end is prefigured in the present. Describing the work of Dan Flavin, he says:

They are involved in a systematic reduction of time down to fractions of seconds, rather than in representing the long spaces of centuries. Both past and future are placed in an objective present. . . . Time becomes a place minus motion.

If time is a place, then innumerable places are possible. . . . A million years is contained in a second, yet we tend to forget the second as soon as it happens. . . . Time as decay or biological evolution is eliminated by many of these artists; this displacement allows the eye to see time as an infinity of surfaces or structures . . .24

Future and past collapse into the present, for the future is already determined; it has been discovered in the increase of entropy taking place before our eyes. This is a devastating attack on the notion of progress, but these ideas also have a deeper and more specific social resonance which Smithson recovered from popular literature.

The 1960s saw the so-called New Wave of science fiction. The New Wave was sparked by a group of young British writers, many of whom often moved in the avant-garde art scene. Much of their work fell into a subgenre of science fiction inaugurated by Wells in The War of the Worlds, and revived by British writers after the war, the global catastrophe novel. For example, in 1966 J.G. Ballard published a novel called The Crystal World, in which time comes to a stop as all matter in the universe begins to grow into crystalline structures. His description of the nature of the disaster reads a lot like Smithson:

We now know that it is time . . . which is responsible for the transformation. The recent discovery of anti-matter in the universe inevitably involves the conception of anti-time as the fourth side of this negatively charged continuum. Where anti-particle and particle collide they not only destroy their own physical identities, but their opposing time-values eliminate each other, subtracting from the universe another quantum from its total store of time. It is random discharges of this type, set off by the creation of anti-galaxies in space, which have led to the depletion of the time-store available to the materials of our own solar system.

Just as a super-saturated solution will discharge itself into a crystalline mass, so the super-saturation of matter in our continuum leads to its appearance in a parallel spatial matrix. As more and more time "leaks" away, the process of super-saturation continues, the original atoms and molecules producing spatial replicas of themselves, substance without mass, in an attempt to increase their foot-hold upon existence. The process is theoretically without end, and it may be possible eventually for a single atom to produce an infinite number of duplicates of itself and so fill the entire universe, from which simultaneously all time has expired, an ultimate macrocosmic zero beyond the wildest dreams of Plato and Democritus.25

As in Smithson's "Entropy and the New Monuments," the science in Ballard’s fiction is a comic pseudoscience used to give his imaginative vision an aura of rationality, but the humor here is really very dark. These English catastrophe novels were typically set in the world of the present, rather than the future, and as a literary phenomenon were deeply rooted in the psychology of the post-war world. Here it is important to recognize the enormous influence that the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament had on British culture in the 1950s, and the involvement in it of many artists, writers, and intellectuals.26 British science fiction writers were acutely aware of the possibility of nuclear war, and unlike many of their American contemporaries, they tried to deal allegorically with the present situation rather than to project a positive future.

One important route by which British New Wave science fiction writers were introduced in America was through a series of anthologies edited by Judith Merrill called The Year's Best S.F. Many writers outside the genre were borrowing science fiction cliches and devices, provoking comment and a proprietary reaction inside the field, and Merrill’s anthologies were partly an attempt to counterappropriate "mainstream" literature to the s.f. genre. They contained stories from writers in the avant-garde and counterculture such as William Burroughs and Tuli Kupferberg; from the art world such as Henri Michaux; fashionable uptown writers one would expect to find in the pages of Esquire or The New Yorker such as Donald Barthelme and John Updike; and young British science fiction writers such as Ballard, Brian Aldiss, and John Brunner. Some of the latter, especially Ballard, were becoming ever more experimental in their technique, aesthetically moving closer to writers such as Burroughs. Smithson would certainly have been aware of Merrill’s anthologies, as their very theme was the relevance of science fiction in contemporary culture.

In The Year's Best S.F. 10 there appeared a story by Ballard called "The Terminal Beach." Predating any of Smithson’s published writing, it contains a number of parallels with Smithson’s concerns, and an astonishing description of what seems to be Minimalist sculpture. The hero of the story is obsessed with Eniwetok, the atoll where the first H-bomb was tested. He travels there and wanders among the now deserted bunkers and airstrips: "One question in particular intrigued him: 'What sort of people would inhabit this minimal concrete city?’" 27 He thinks of his wife and child, killed in an auto accident:

The Pre-Third: this period was characterized in Traven’s mind above all by its moral and psychological inversions, by its sense of the whole of history, and in particular of the immediate future - the two decades, 1945-65- suspended from the quivering volcano’s lip of World War III. Even the death of his wife and six-year-old son in a motor accident seemed only part of this immense synthesis of the historical and psychic zero, the frantic highways where each morning of his life they met their deaths on the advance causeways to the global Armageddon.

Here the experience of time as an unending repetition of the same is explicitly described as the condition of the post-war world. He makes his way to ground zero where he finds a field of concrete bunkers:

There were some two thousand of them, each a perfect cube 15 feet in height, regularly spaced at ten-yard intervals. They were arranged in a series of tracts, each composed of two hundred blocks, inclined to one another and to the direction of the blast. They had weathered only slightly in the years since they were first built, and their gaunt profiles were like the cutting faces of some gigantic die plate, devised to stamp out rectilinear volumes of air the size of a house.

The concrete bunkers resemble the space displacing cubes of Robert Morris, or a lattice by Sol LeWitt:

Three of the sides were smooth and unbroken, but the fourth, facing away from the blast, contained a narrow inspection door.

It was this feature of the blocks that Traven found particularly disturbing. Despite the considerable number of doors, by some freak of perspective only those in a single aisle were visible at any point within the maze. As he walked from the perimeter line into the centre of the massif, line upon line of the small metal doors appeared and receded, a world of closed exits concealed behind endless corners.

This description has an uncanny relevance to Smithson’s own work, particularly to his incorporation of perspective effects in his sculpture:

Approximately twenty of the blocks, those immediately below ground zero, were solid; the walls of the remainder were of varying thickness. From the outside, however, they appeared of uniform solidity.

Ballard’s description even recalls the common observation that from the outside, it is impossible to tell whether a Tony Smith or a Robert Morris cube is solid or hollow.

Since the story must have been written before 1965, in Britain, Ballard could not have known anything about Minimalist art; Judd was just beginning to exhibit in 1964. But Smithson could hardly have overlooked the remarkable similarities between the concrete details of Ballard's fantasy and the work of his friends. It was because of this kind of connection that Peter Hutchinson, another artist and friend of Smithson, could write in 1968 that "Strangely enough, the illustrative art of science fiction . . . is remarkably old-fashioned . . . It would make more sense to find contemporary art by Donald Judd, Larry Bell, Robert Smithson and Lila Katzeri, for example, published in these magazines.’’32

But in Ballard’s writing, science fiction annihilates itself by declaring that there is no future:

The series of weapons tests had fused the sand in layers, and the pseudo-geological strata condensed the brief epochs, microseconds in duration of thermonuclear time. Typically the island inverted the geologist's maxim. The key to the past lies in the present/ Here, the key to the present lay in the future.

For Ballard, time stops when one realizes that the present can only be understood as a preparation for the inevitable future apocalypse. All life is suspended between the first bomb and the last, future and past both collapse into the present where the lifeless geometric landscape is an image of eternity. In Ballard’s reversal of the geologist’s maxim lies the key to science fiction as a fantasy of the future that contains the hidden truths of the present.

Though not widely reprinted, "The Terminal Beach" and Ballard himself have enjoyed a long underground reputation in the art world. Ballard's story is independent confirmation of the perfect contemporaneity of Minimalism, and it widens the network of literary accretions that work received in Smithson’s writing. Smithson never spoke didactically, he would never have baldly equated the "psychic zero" of Minimalism with ground zero at Eniwetok, yet Ballard’s understanding

that the sense of stopped time is a phenomenon of a specific historical period, with a concrete social cause, creates a further level of contextualization that Smithson tacitly acknowledges in a 1968 article under the subheading "Spectral Suburbs:"

It seems that 'the war babies’, those born after 1937-38 [Smithson was born in 38] were 'Born Dead’ - to use a motto favoured by the Hell’s Angels. The philosophism of 'reality' ended some time after the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the ovens cooled down.

Earlier I suggested that Smithson’s linking of Minimalism and contemporary architecture contains an implicit recognition of the ambivalent position of Minimalism in the culture. This critique is made possible by the same phenomena that gave Minimalism itself its potentially critical edge—the absence of any interior to the work and the blank surfaces that throw the spectator back on the relationship between him- or herself and the exhibition space. But just as the recognition of its similarity to architecture inflects his reading of Minimalism, so Smithson looks at contemporary architecture with the same objectifying gaze demanded by Minimalist sculpture. "The Domain of the Great Bear," a piece co-written with Mel Bochner, describes the banal theatrical effects created in various rooms of the Hayden Planetarium. Repeatedly Smithson steps back, objectifying the planetarium’s illusions, and once more finding the inert, the vacant, and the entropic:

The cycle of the planets occurs and reoccurs. The solar system, this mechanical collection of tracks, boxes, bulbs, gears, armatures, rods, seems tired, torpid. A chamber of ennui. And fatigue. It is endless, if only the electricity holds out.35

In a two-page "Minimalist" layout, Bochner and Smithson arrange photos of the motors that drive the replica of the solar system and the outside of the planetarium dome under construction in an inverse relationship with boxes of lists ironically labeled "the secrets of the domes," and "the secrets of the ambulatories." For Smithson, there are no inner metaphysical secrets, and he refuses to remain inside any system, locating all transcendent concepts, such as infinity, in the world of objects.

Bochner and Smithson’s visit to the planetarium occurred during its renovations. The obsolete future of the 1930s was being replaced by the space age of the 1960s:

. . . The light of recently installed exhibitions is bleaching out the dim uncertainties of 1934. New notions of the future and space, more optimistic and satisfying, are supplanting the dreary void. Formica and fluorescent, chrome and plexiglass are replacing the beaverboard, textured cement, glass and plywood. The dismal maroons and blacks are being repainted acqua, chartreuse, cerise or tangerine.

Just as the science fiction of the 1930s, saturated with visions of entropy, was replaced by the technological problem story, so the space-age newness of post-war consumer society buries the future dreams of the pre-war world with its social utopias and its cosmic pessimism. But for Smithson, "The conundrum, however, remains."37

The recovery of the sensibility of the 1930s is the theme of another of Smithson’s pieces on urban architecture, "Ultramoderne." This article contains numerous references to George Kubler’s The Shape of Time. Kubler asserted that art objects lay on a continuum with other man-made things, and his book attempted to define the categories of a formal history of things, their repetition and variation in time and their classification in series. His formalistic approach ignored symbolic and affective content, recognizing only the "exterior" of objects. He also sought out relationships of form between objects found in widely different cultures and historical epochs.

In "Ultramoderne," Smithson treats the surfaces of 1930s architecture to a Kublerian reading, but he can’t help picking up traces of a social history in these buildings. His attempt to objectify them as the historical exterior of his own period fails to the extent that they open up to an ongoing history. As Kubler himself says:

. . . we cannot clearly descry the contours of the great currents of our own time: we are too much inside the streams of contemporary happening to chart their flow and volume. We are confronted with inner and outer historical surfaces. Of these only the outer surfaces of the completed past are accessible to historical knowledge.

The opening sentence of Smithson’s essay exposes the historical strata:

The Ultramoderne of the thirties transcends Modernist /historicistic, realism and naturalism, and avoids the avant-garde categories of 'painting, sculpture and architecture’. A trans-historical consciousness has emerged in the sixties, that seems to avoid appeals to the organic time of the avant-garde and that is why the thirties are becoming more important to us. Even Clement Greenberg says the avant-garde is suffering from 'hypertrophy’ (the organic metaphor is accurate) . . . The Ultraism of the thirties escapes the plague of 'social realism’ of the same period, and the reaction of organic or naturalistic 'abstract expression’ in the fifties.39

These buildings provoke Smithson’s own argument with a criticism that he felt was mistakenly preoccupied with a metaphor of art as a historical process of growth and development, and an art history that projected that development in a linear fashion. He makes a particularly penetrating observation concerning the relationship of the New York school to its own prehistory: "All that was fascinating about the so-called Surrealists was subverted by a kind of "abstract naturalismr that imagined itself form al/" 40 Jackson Pd lock’s derivation from Andre Masson’s automatism became the touchstone of a school that forgot the intent of surrealism in the formalism of the abstract field. But what Smithson doesn’t quite see is that the forgotten history sealed in the walls of the Ultramoderne is political, and that the architecture of the 1930s, " . . . a cosmos that dissolves into fatigued and tired distances," is historically bonded to social realism.41

We now know very well that the modernism of the New York school was built on a repudiation of much that happened in the 1930s. There is a break in continuity that renders the ’30s inaccessible to us today. Socially, that break is the collapse of the left in America. The '30s was the last period of a general belief in the coming utopia of socialism, but as I have indicated already, fantasies of utopia were always interwoven with a fatalism derived from science itself. In socialist theory, scientific and technical progress were seen as necessary preconditions of social evolution, but science teaches that the universe, and hence all social life, is ultimately subject to entropy.

The R.C.A. building at Rockefeller Center contained a mural by Diego Rivera that was destroyed on the instructions of Rockefeller himself because it contained a portrait of Lenin. The mural was Rivera’s interpretation of a theme set by the architects: "Man at the Crossroads Looking with Hope and High Vision to the Choosing of a New and Better Future."42 The central section of the picture was an image of cosmic sweep, worthy of the best science fiction of the period. Two long, narrow ellipses crossed at the centre of the mural, and at the crossing a hand held a glowing sphere containing images of the splitting of the atom and cell division. Humanity, in the socialist vision of the future, controls the physical universe and human evolution. One of the ellipses was filled with biological imagery, the other contained astronomical bodies. The mural as a whole was divided in two at the middle, one half depicting the present world of fascism and monopoly capital, the other half the positive forces of socialism. The two ellipses also followed this pattern, and the "bad" side of the cosmic ellipse was filled with the entropic images of a dead moon and an eclipsed sun. This painting illustrates perfectly the role that scientific speculation played in the socialist imagination of the period, and further, that utopian dreams were always haunted by the cosmic pessimism of entropy. Yet this fatalistic attitude was certainly also rooted in a series of contemporary defeats; Rivera layered his entropic imagery firmly across scenes of a troubled present. These defeats are themselves symbolized by the destruction of the mural. The dream of a future captured by socialism was forestalled in America by deeply entrenched present interests. Smithson notes with devastating yet perhaps unconscious insight that "The walls of these forgotten buildings from the Riverside museum to Radio City bring one face to face with the incredible features of something immortal yet corrupt."43

With the collapse of a viable socialist context against which to read the architecture of the 1930s, all that is left are a series of objects in which Smithson can yet see the traces of . . the obsolete future of H.G. Wells' Things to Come," and entropic infinities in "The arduous limits of the Empire State (which) fill one with thoughts of extinguishment and vertigo/’44 These descriptions mark the limit of Smithson’s ability to objectively contextualize the phenomena of his own time. He instinctively recognizes the "Ultramoderne" as antithetical to New York School Modernism, as is the work of his friends the Minimalists, but the human history of the period, and an understanding of the break between that period and the later is lost to him. He recognizes a link between the sensibility of the 1930s and that of the 1960s, but he doesn’t clearly see that as the resurfacing of a repressed history. He is aware that the post-war illusion of progress, the "organic time of the avant-garde," cloaks an inert, entropic, unchanging present, but can’t quite see that as the persistence of social reaction.

Smithson’s urban landscape is always empty of people; their works appear as if "ab aeterno."45 Smithson apprehends architecture as a phenomenon of nature, like geological formations. His strategies, such as showing the planetarium dome under construction, combined with the literary grounding of many of his ideas, tantalize us with glimpses of the social world, yet Smithson never, in the 1960s at least, explicitly deals with the human relations that make up that world. He never confronts the specific forces that determine the character of the city, the economic interests that both display and conceal themselves everywhere within it.

He is always external to the objects of his study, and in this his strategy is quite different from that of the Surrealists forty years before.

The Surrealists also encountered the city as a kind of nature, for when their imaginations were stimulated by some chance encounter in a flea market or a piece of architectural detailing, they of necessity had to forget the social production of that object in order to see it as strange. Salvador Dali’s "discovery" of Hector Guimard’s Metro entrances is a parallel with Smithson’s interest in the "Ultramoderne." An object has survived the passing of its original social context, to find a new life in the imagination. But this imaginative play with the manmade world can release from the object traces of its forgotten social history. This potential in the Surrealist game was noticed by Walter Benjamin and later developed by the Situationists, who began with the derive, a surrealist-inspired urban walking tour, and progressed to a systematic critique of the city, now seen as a concretization (and producer) of ideology.46 The Situationists recognized the social history buried in objects to be the social relations concealed by the urban structures they inhabit.47 Smithson, on the other hand, doesn’t try to penetrate the urban spectacle, or to release any memories from it, though as we have seen, they seep out anyway; his strategy is to envelop or contain all objects in a progressively more complete objectification. He is always going back another step, trying to get a look at the outside of whatever context he is in. His particular brand of flanerie has a typically American positivistic flavor, yet in its own way his objectifying vision of the city does expose its inner mechanisms, and to this extent Smithson’s thought is complementary to that of his Situationist contemporaries. Springing from different roots, belonging in different cultures, these two independent urban critiques work together to form an image of the city today. They do, however, have one point of contact, the ideas of Lewis Mumford. Mumford originated the concept of the spectacle, later taken up by the Situationists,48 and his writings on suburbia are quoted extensively in Guy Debord's Society of the Spectacle, first published in ^ 967.49 Mumford’s analysis of suburbia is very relevant to Smithson, and in fact we can see the beginnings of a more pointed critique in his work as he shifts his attention outside the city.

Smithson had already described a visit to suburban New Jersey in "The Crystal Land," published in the summer of 1966, where he found the so-called meadowlands to be " . . . a good location for a movie about life on Mars . . . Drive-ins, motels, and gas stations exist along the highway, and behind them are smoldering garbage dumps/,50 Then Tony Smith's description of a night drive on the unfinished New Jersey Turnpike appeared in Artforum at the end of the year, and it must have quickened Smithson’s interest in the suburbs.51

When I was teaching at Cooper Union in the Fifties someone told me how I could get on to the unfinished New Jersey Turnpike. I took three students and drove from somewhere in the meadows to New Brunswick. It was a dark night and there were no lights or shoulder markers, lines, railings, or anything at all except the dark pavement moving through the landscape of the flats, rimmed by hills in the distance, but punctuated by stacks, towers, fumes, and colored lights. This drive was a revealing experience. The road and much of the landscape was artificial, and yet it couldn’t be called a work of art. On the other hand, it did something for me that art had never done. At first, I didn’t know what it was, but its effect was to liberate me from many of the views I had had about art. It seemed that there had been a reality there which had not had any expression in art.

The experience on the road was something mapped out but not socially recognized. I thought to myself, it ought to be clear that’s the end of art. Most painting looks pretty pictorial after that. There is no way you can frame it, you just have to experience it.

Later I discovered some abandoned airstrips in Europe abandoned works, Surrealist landscapes, something that had nothing to do with any function, created world without tradition. Artificial landscape without cultural precedent began to dawn on me. There is a parade ground in Nuremburg, large enough to accommodate two million men. The entire field is enclosed with high embankments and towers. The concrete approach is three sixteen inch steps, one above the other, stretching for a mile or so.

First of all, Smith notes that painting seems to be inadequate to represent this landscape; its size and power exceed the capacity of the hand-made image.

But the sheer size of the landscape is not enough to defeat its representation, for deserts, mountains, and oceans have all been painted. In fact, though Smith acknowledges that this landscape is man-made, he apprehends it as a kind of nature, or rather as nature is apprehended by the casual tourist from the city, as a spectacle of grandeur remote from human concerns. But this is a human landscape, and it is precisely the kinds of relationships inscribed in it, relationships of domination, control, ownership, and exploitation, that make it so alienating. The landscape itself doesn’t overpower its spectator, it is the society that has altered that landscape into an enormous spectacle of human indifference that reduces him to nothing in front of it. The defeat of the individual subject by a mass industrial society whose organization he understands in principle but whose actual workings are beyond his grasp has been accomplished; it is only a corollary that the representation of the social landscape in painting, bound up as that medium inevitably is with an individual subjectivity, is also defeated in advance.

Many elements of Smith’s description recall the Surrealists. The industrial landscape evokes the immense empty perspectives of the parade ground at Nuremburg, an image reminiscent of a piazza by de Chirico. As for the Surrealists and for Benjamin, for Smith the manmade landscape evokes a fantasmic dream image which contains hidden social meanings. Smith’s linking of the New Jersey meadows with Nuremburg has a shocking resonance, for Nuremburg is not just another place on the map, but a site redolent of fascist domination and terror. In Smith’s astonishing free association, we can see the American landscape give forth involuntarily a ghostly image of its own inner truth; the social content of the landscape is an economy based on the weapons industry and the maintenance of a state of nuclear terror. But the parade ground, which Smith visited in the early 1950s, is deserted. As in Smithson’s writing, the social and historical dimension is evoked in terms of huge vacant spaces, of enormous vanishing perspectives, of timeless epochs containing both the past and the future but empty of human life.

In another interview published at the same time,

Smith indicated that the urban fringes were a fitting site for his own work. According to Smith:

. . . the social organism can assimilate them only in areas which it has abandoned, its waste areas, against its unfinished backs and sides, places oriented away from the focus of its well-being, unrecognized danger spots, and unguarded roofs.

These remarks have implications for Smithson’s later non-sites, but first I will examine his article "A Tour of the Monuments of Rassaic, New Jersey, published in December 1967, which is partly a response to Smith’s short description of New Jersey and an attempt to take up the challenge of representing that landscape in a literary form.

Like Smith, Smithson begins by asserting the inadequacy of painting to represent the modern world, but he flavors his attack with ridicule. A landscape by Samuel F.B. Morse was reproduced in the New York Times art page the day of Smithson’s trip to Passaic; Smithson reproduces the newspaper photo of the painting, itself a degenerate image two steps removed from the original, forcing the image further into illegibility in a demonstration of the entropy of information. He says, "The sky was a subtle shade of newsprint grey."54 His recounting of John Canaday’s art column is a deliberately, or perhaps simply indifferently, garbled melange of misattributed and displaced quotations: ^Canaday referred to the picture as standing confidently along with other allegorical representatives of the arts, sciences and other high ideals that universities foster.’’55

The monuments of Passaic inhabit ruined landscapes such as construction sites and unfinished highways. For Smithson, these ruins evoke romantic painting, and the absurdity of the equation renders both of its terms ludicrous. "Actually, the landscape was no landscape, but . . . a kind of self destroying postcard world of failed immortality and oppressive grandeur.”56 But then:

. . . I saw a green sign that explained everything:

YOUR HIGHWAY TAXES 21 AT WORK

Federal Highway U.S. Dept, of Commerce

Trust Funds Bureau of Public Roads

2,867,000

New Jersey State Highway Dept.

That zero panorama seems to contain ruins in reverse, that is all the new construction that would eventually be built. This is the opposite of the 'romantic ruin' because the buildings don’t fall into ruin after they are built but rather rise into ruin before they are built. This anti-romantic mise-en-scene suggests the discredited idea of time and many other 'out of date’ things. But the suburbs exist without a rational past and without the 'big events' of history. Oh, maybe there are a few statues, a legend, a couple of curios, but no past—just what passes for a future. . . . A Utopia minus a bottom. . . . Passaic seems full of 'holes’ . . . and those holes are the monumental vacancies that define, without trying, the memory-traces of an abandoned set of futures. Such futures are found in grade B Utopian films, and then imitated by the suburbanite.

The theme of stalled time, of halted progress, that runs through all of Smithson’s writing like a scratch on a record, here begins to take on a more concrete social meaning in relation to repressed or forgotten possibilities:

I’m convinced that the future is lost somewhere in the dumps of the nonhistorical past; it is in yesterday’s newspapers, in the jejune advertisements of science fiction movies, in the false mirror of our rejected dreams.

The "Tour" is a devastating satire of the American city. To Smithson "Passaic center was no center, it was instead a typical abyss or an ordinary void." In truly entropic fashion, Smithson’s tone becomes bleaker and his descriptions more enervated as he reaches the end of his article. The last monument is the sandbox:

. . . this monument of minute particles blazed under a bleakly glowing sun, and suggested the sullen dissolution of entire continents, the drying up of oceans— no longer were there green forests and high mountains, all that existed were millions of grains of sand, a vast deposit of bones and stones pulverized into dust.

The banality of the sandbox and the hyperbole of the description combine to make an inverted romanticism of entropy, but when he observes that the . . sandbox doubled as an open grave—a grave that children cheerfully play in," the social critique becomes truly savage.

The sandbox then serves for "a jejune experiment for proving entropy:’’

Picture in your mind’s eye the sandbox divided in half with black sand on one side and white sand on the other. We take a child and have him run hundreds of times clockwise in the box until the sand gets mixed and begins to turn grey; after that we have him run anti-clockwise, but the result will not be a restoration of the original division but a greater degree of grayness and an increase of entropy.

Of course, if we filmed such an experiment we could prove the reversibility of entropy by showing the film backwards, but then sooner or later the film itself would crumble or get lost and enter the state of irreversibility. Somehow this suggests that the cinema offers an illusive or temporary escape from physical dissolution. The false immortality of the film gives the viewer an illusion of control over eternity- but ’the superstars’ are fading.

This final lugubrious recounting of the inevitable progress of entropy is a fantasy of revenge on an oppressive and meaningless world. Entropy has two faces for Smithson; it is the underlying principle of the social world where progress is really obsolescence, where the myth of evolutionary change cloaks the static reality of a frustrated utopia, but it is also an underlying principle of the physical universe, and from a vantage of millennia, the artist can transcend the depressing contingencies of history and appreciate the ultimate futility of action.

Smithson’s urban requiem has to be seen in the context of contemporary discussion about the cities. In 1967 America seemed to be coming apart at the seams. A huge antiwar demonstration had marched on the Pentagon that spring. During the summer ghettos all over the country, but above all in Newark, only a short drive from Passaic, had exploded into violence. Throughout the '60s an awareness of the decay of the inner cities and of the growth of slums and poverty had been growing. In 1962 Michael Harrington published The Other America. Harrington carefully kept his account to the "facts," avoiding any in-depth analysis of the economic system that creates slums in the first place. Because of this the book spoke strongly to liberals, who were shocked at the existence of widespread poverty in America, and helped to provoke various "great society" programs such as affirmative action and job creation in the inner cities. At the same time, redevelopment schemes began to spring up, and there were new attempts to plan suburban growth with a view to the quality of life. A special issue of Life devoted to the city had appeared in December of 1965, one year before Dan Graham’s "Homes for America" and six months before "The Crystal Land." It included articles on slums and urban sprawl, but tended to focus on redevelopment, with a generally upbeat tone. A critical look at this magazine clearly reveals the simultaneous tendencies of growth and decay in the urban landscape and also the kind of ideology that obscured the relationship between them. The lead article was a cheerful catalog of incongruities and eyesores called " No one’s in charge.’’ A correspondent travels to the suburbs to . . inhale the stench of the New Jersey 'meadowlands' with their oil refineries and open dumps . . .’’61 Announcing in the lead line that "the villain is you," the article takes a tour of the messy edges of the city and then concludes that no matter how much Americans may hate pollution and urban sprawl, they really must like them because America is a democracy:

Call it by any name, chaos, unplanned growth, ribbon development, social anarchy, slurbs, the decline of American civilization, the resurgence of laissez-faire, but recognize it for what it is—— a people’s laissez-faire, which sinks its roots down past any rotting level of corrupt and cynical behaviour by the few into a subsoil of widespread popular support and an abiding tradition of private property, individual freedom and 'every-man’s-home’s-his-castle.

The tradition of liberal democracy holds that people can organize collectively to determine the quality of their lives. Yet the impression remains, and Life magazine is certainly intent on creating that impression, that nothing can ever really change. This ideological closing off of possibilities is even clearer in an article on "Cities of the Future," which projects decentralized, small, semi-rural communities with lots of green space, and, on the same page, "buildings large enough to qualify as cities in themselves."63 Utopia is a few cliches cobbled together by a staff writer who can’t decide whether it is to be the dream suburb or the nightmare city.

No matter how society is organized, entropy continues to increase on the physical level, and that fact has immense social implications that were just beginning to be recognized in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The following quote from a popular book on entropy published in 1967 lays out the basis for the application of the concept in the social sciences:

Some scholars recognize society itself as a force that tends to produce order out of disorder, thus producing large scale, but local, entropy reductions . . . even though society can effect local reductions in entropy, the general and universal trend of entropy increase easily swamps the anomalous . . . effects of civilized man. Each localized man-made or machine-made entropy decrease is accompanied by a greater increase in entropy of the surroundings, thereby maintaining the required increase in total entropy.64

Entropy means the dispersal and therefore loss of available energy, . . population is the sum total of all the available energy that has been transformed into unavailable energy."65 The liberal view is that through cooperation and planning, the dirty can be cleaned up, the messy can be tidied. Progress means amelioration, the gradual perfection of a basically sound system. Politically the view may be naive, but scientifically it is even more so. Progress is out of the question, and the only way to slow down decay is to minimize the amount of energy that flows through the system, in other words, to slow down growth, for more growth means more decay. This is the conclusion that Life intends to avoid by its free enterprise rhetoric.

A less ideological, more honest criticism of the cities than that in Life could be found in the writing of Lewis Mumford. Mumford, the foremost historian of the city, had an acute sense of the interrelation of all the parts making up the modern conurbation. Unlike the writers in Life, Mumford clearly identifies the actual mechanisms behind the production of urban sprawl. Inner city decay and redevelopment and the growth of suburbs are interrelated parts of an organic whole. Though not explicitly identified as entropy, Mumford’s discussion of "Abbau" or unbuilding, a concept he picked up from the entomologist William Morton Wheeler, is really the same thing:

The process of unbuilding . . . is not unknown in the world of organisms. . . . In unbuilding, a more advanced form of life loses its complex character; there is an evolution downward, toward simpler and less finely integrated organisms. There is/ observed Wheeler, 'an evolution by atrophy as well as by increasing complication, and both processes may be going on simultaneously and at varying rates in the same organism/ . . . A process of up-building, with increasing differentiation, integration, and social accommodation of the individual parts in relation to the whole was going on . . . an articulation within an everwidening environment was taking place within the factory, and indeed within the entire economic order. . . . But at the same time, an Abbau, or un-building, was taking place, often at quite as rapid a rate, in other parts of the environment: forests were slaughtered, soils were mined, whole animal species were wiped out. . . . Above all, this unbuilding took place in the urban environment.66

Smithson’s recognition of the similarity of a construction site and a ruin, the "buildings that rise into ruin before they are built, catches the cycles of simultaneous upbuilding and un-building at their intersecting nodes.

For Mumford, the actual agent of urban decay is the automobile, and the freeway system that links the city to its surroundings. He describes how the modern suburb, built around the highway, creates social fragmentation and isolation. The speed and reach of the automobile paradoxically fails to unite people, but rather strands them in a wasteland of parking lots, malls, and freeways. The needs of the automobile require huge amounts of space and so the city expands and disperses to accommodate them. This process works back on the urban core—as increasing numbers of people flow in and out every day, freeways and parking facilities take up a larger share of urban space and the city itself takes on the empty character of the suburbs: a nexus of traffic rather than a center of life. The highways that bring the resources of the country to the city as a center of administration, economic growth, and power, are also the channels through which the life of the city drains and disperses into the suburbs. The entropy of the city is found not only in its pollution, but in the break-up of social life and the leveling of city and country into an undifferentiated unity.67

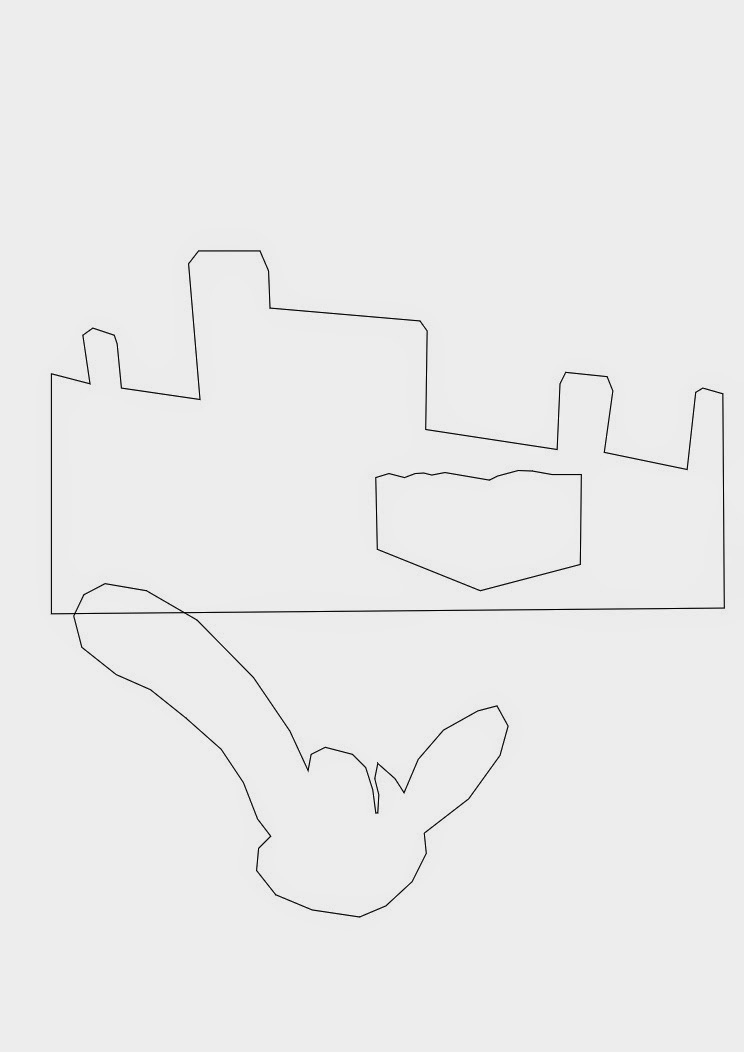

These ideas find an echo in a study of Smithson’s titled " New Jersey/New York,” a map of the area straddling the state line with the center cut out (fig. 1). Around the left edge we find suburban towns such as Passaic and Bayonne, and on the opposite side, Brooklyn and the South Bronx. The plunging perspectives of the Polaroid photos of freeways point into the empty center where Manhattan would be. But exactly balancing Manhattan within this empty space are the meadowlands of New Jersey, already noticed for their pleasant mixture of burning garbage dumps and oil refineries. In the language Smithson used to describe Passaic, "a typical abyss, an ordinary void" embraces both sides of the city, the center and its emblematic suburb, the meadowlands.

The meadowlands, a disorganized area traversed by freeways going elsewhere, had a special significance for Smithson as the entropic antipode to New York. A small drawing of 1967 places a grid over the meadowlands centering on Seacaucus, which Smithson has labeled "entropic pole/’ Because of its nearness to Manhattan, because of its familiarity to Smithson from his trips between the city and his childhood home in Clifton, N.J., and because it was the terrain of Tony Smith’s famous midnight drive, the meadowlands is exemplary of that characterless and indeterminate no-man’s니and between the city and the suburban towns in which Smithson found the material for his so-called non-sites.

A photo piece of 1968 called "Dog Tracks, associated with one of the non-sites, is another work based in the meadowlands area around Seacaucus. In a kind of "portrait of the artist as suburban explorer" a photograph of a mud puddle is overexposed so that its center is a burned out void, and around this emptiness are dog tracks indicating a confused multiplicity of possible paths.

For Smithson, the linking of city and suburb was graspable as a dialogue between center and edges, in which, like the Chinese concept of yin and yang, one is always in the process of changing places with the other. In the non-sites, a series of sculptures begun in the months following the Passaic trip, Smithson collected rocks from a marginal, abandoned site, such as a disused quarry, a landfill, or slagheap, and put them in containers, the shapes of which continued the concerns of his earlier Minimalist sculptures. When he showed these pieces in a gallery, they were accompanied by a description or a map that drew a clear link between the gallery piece and the original site (fig. 2). For Smithson the original sites were . . open and really unconfined and constantly being changed . . .”68 . . yet if art is art,

it must have its limits. How can one contain this 'oceanic’ site? I have developed the non-site, which in a physical way contains the disruption of the site.’’69*The geometric containers that hold the material selected from the site effectively put a frame around a section of the world. They are Smithson’s answer to the challenge in Tony Smith’s statement that, "There is no way to frame it, you just have to experience it."

As portable objects they are literally non-sites, but they also identify the abstract space of the gallery, a place with no particular character, that exists only to refer to other places. Smithson brings out the fact that the gallery is always a non-site, just as the consciousness of the urban dweller is always split between his or her physical location and somewhere else. The common experience of city life is of a multitude of insubstantial, abstract spaces, and the gallery is a specialized display area for the abstract spaces and fantasy locations we call art. The neutrality of the gallery serves as the screen for the projection of any number of imaginary spaces, and the ideological nature of this functioning lies at the root of all political critiques of the gallery space, for the greatest neutrality always conceals very partisan interests. The critique of the gallery, however, becomes trivial when it devolves into a phenomenological investigation of the actual physical space. It also loses its effectiveness when it descends to the mechanistic level of attributing specific political meanings to that physical space, asserting that liberation can only be found outside. Smithson’s critique of the gallery involves opening it up to the world. It’s as if the city has sprung a leak, allowing the entropic outflow of the edges to flow back in a circular movement. The center and the edge change places, for the suburbs are the genuine non-site, without character, "a typical abyss, an ordinary void." In this sense, Smithson’s designation of the gallery pieces, and by extension the gallery itself, as a non-site is a sarcasm directed at the city. The suburb, in that it reveals the entropic nature of the city, is the real center.

There is no potential in the materials used in the nonsites, they are the end products of geologic or social processes, and completely useless. In Non-Site: Line of Wreckage (Bayonne New Jersey) (fig. 2), of 1968, for example, the material is rubble collected from a landfill—the remains of demolished structures. The containers of the non-sites resemble Minimalist sculptures rendered transparent. Smithson’s gloss of Minimalism as entropic here ceases to be a literary notion. One sees through the inert primary structure to the material ground on which social life is based and to a concrete demonstration of entropy. The result is a kind of picture. Non-Site: Line of Wreckage is accompanied by a grid of Polaroids taken at the site. The grid could be called a cognitive frame, a container or form for our knowledge. In this case the contents are highly entropic, and for Smithson it’s certain that the evenness of the grid has the effect of further draining the image of meaning. We can see his humor at work here, as well as an anticipation of the current fashion to replace knowledge with "information." But further, the grid of photos and metal container of rubble work together to make a highly pictorial work. Even the gradual diminishment of the width of the slats of the box suggests a residue of perspective.

The critical nature of the non-sites, like that of Minimalist sculpture, lies in a dialogue between the object and its context, but it is much harder to treat the non-sites as discrete aesthetic objects. Their context is larger, comprising the total system of the city and its surroundings, and the objects themselves are more complex, including reference to a process of transformation, entropy, with specific implications for the social world, and to another space beyond the gallery, not the idealist and immaterial space referred to by an abstract expressionist painting, for example—that is, the subjectivity of the artist—but a place as real and material as any Minimalist sculpture. Smithson, like Judd and the others, wants to have done with illusionism, yet the decisive feature of the non-sites as a critical art is their character as framing devices. Whereas Minimalist sculptures, as Smithson’s own critique implies, are part of an undifferentiated site including the man-made world as well as the geological, the non-sites as frames reintroduce the possibility of a critical distance on the world and on the ideology that holds that the social world is "natural." Without returning to representation, Smithson found a way to reestablish the dialectical synthesis of form and content that had always been the goal of art, but which was lost in the positivistic emphasis on the object characteristic of Minimalism.

conflict in the cities reached its greatest pitch. The nonsites gain a critical distance from the highly politicized city by their grounding in the urban margins, yet their content is still the primacy of entropy in and over the social realm, and they express a skepticism towards the notion of material improvement. Mumford hit the right pessimistic note:

This negativity is in stark contrast to the attitudes of many of Smithson’s peers. In 1962 a convention of left-wing student groups drafted the "Port Huron Statement," the founding charter of the Students for a Democratic Society.71 This document marks the rebirth of the American Left after the Cold War period, and at the same time a break between the old Left and the young generation. The framers of the statement were clear that their criticisms of America grew out of belief in the ideals of a liberal democratic society, and a sense of disappointment that America didn’t live up to these ideals. To them, the nation was perfectible, and at the beginning at least, the movement to change America was a movement of reform. The old revolutionary Left, with its highly developed theoretical basis had been virtually wiped out through a combination of repression, judicious expansion of the wartime economy, and the restructuring of all aspects of American life in the mass consumer society. Not least in importance in this respect was the dispersal of the population into the growing suburbs. A kind of hyper-Haussmannization took place, in which people were effectively isolated from one another while their consciousness was being joined by a centralized mass media controlled from the top.72 In its early period, the New Left visualized change through political parties, grass roots organization, interest groups, letters to congressmen, informing the public through the media, and all the other paraphernalia of representative democracy. Smithson could not take this kind of political life seriously. He found no common ground with the activists of his generation, and as the movement became more radical and moved toward violence, he distanced himself even further, moving his work further into the countryside. Yet from his teenage admiration of the Beats to his lugubrious celebration of Minimalist inertia, Smithson had always been disaffected, and like that of his peers in the student movement, Smithson's criticism of America had to evolve out of what America had given him.

Smithson’s thought developed through exposure to a constellation of thinkers who, if not all positivists, all placed an emphasis on the concrete. William Carlos Williams was Smithson’s pediatrician, and his long narrative poem Paterson was an early inspiration. Paterson uncovered the layers of human and geological history of this New Jersey town and its environs, from colonial days to its later submergence in megalopolis. On the first page Williams quoted Pound’s famous dictum, "no ideas but in things."73 The link with Imagism is important, for T.E. Hulme, the theorist of that literary movement, was an early and very important influence on Smithson. For Hulme, phenomena were real but concepts not; abstractions were "approximate models," simple direct images came closer to concrete reality.74 Smithson would have received these ideas in the context of Hulme's art historical theories, derived from Wilhelm Worringer, especially his linking of nonobjective art with prehumanist, pre-Renaissance art. Smithson later acknowledged Hulme’s influence as crucial for his development away from biomorphic gestural abstraction towards Minimalism. As Smithson began to think about an abstraction based on the crystalline geometries of nature, he found a compatibility with the Minimalists, some of whom, particularly Judd with his blanket refusal of any meaning outside of the object itself, were genuine positivists. In the meantime his scientific reading included P.W. Bridgman, originator of "operational analysis," an empiricist dogma that asserted that all concepts can be reduced to "operations." Later he was attracted to the formalist categories of George Kubler. Yet Smithson’s drive to . . understand the system I’m being threaded through," joined to that typically American positivistic emphasis on objects and surfaces, led him to try and objectify every conceptual system that he studied. It was this skeptical and objectifying attitude that underlay his theorizing of Minimalism in opposition to New York School abstraction, and that further allowed him to notice the resemblance between Minimalist objects and urban architecture, k was again this attempt to step outside his context that brought him to the outskirts of the city, to find there the evidence of the entropic processes working at its core. It also allowed him to rationalize an indifference to partisan politics on the basis of the primacy of physical processes such as entropy. This progressive attempt to step back finally led him to realize that there is no way out, that the edge leads back to the center again, and the understanding of a dialectical approach that can contain contradictory movements; but again it was his determination to concretize his insights that led him to construct that dialectic materially in the non-sites.

From the non-sites onward, Smithson’s awareness of social issues becomes more acute, and he becomes more willing to pronounce on them, especially on the politics of art. Towards the end of his life, he was beginning to describe himself as a Marxist. Perhaps this was due to the influence of texts he read in the early 1970s, but any later influences he received would have fed into the ongoing development of his thought. Finally, this is what makes Smithson so interesting and relevant as a social critic, that out of the positivist tradition in American culture, he developed an art that reflected profoundly on social realities.